Flies have tiny wings and even tinier brains, yet they are capable of flying swiftly and agilely through even turbulent air. How do they do it?

And could we create a robot capable of doing the same?

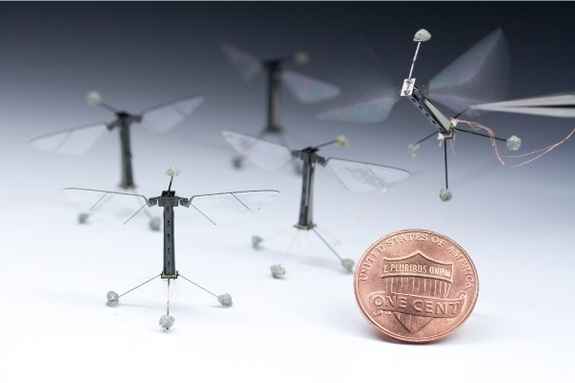

That’s the question that’s been buzzing around Harvard professor Robert Wood’s head for 12 years now. And finally, after years of testing and the invention of an all-new manufacturing technique inspired by children’s pop-up books, Wood and his team at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have created a robot the size of a penny that is capable of remote-controlled flight.

You’d think that the smaller something is, the easier it’d be to make. But there’s a point at which making things smaller becomes harder rather than easier, which is why making a functional fly-sized robot has proved such a challenge.

The so-called RoboBee flaps its wings approximately 120 times per second, almost faster than the eye can track, and is capable of hovering and flying horizontally in multiple directions like a helicopter.

At 80 milligrams, which is less than one-twentieth the weight of a dime, the robot is so small that traditional components of flight-capable machines simply wouldn’t work, so the team had to create new ones.

“Large robots can run on electromagnetic motors, but at this small scale, you have to come up with an alternative, and there wasn’t one,” Kevin Ma, a co-lead author and graduate student at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, said in a statement.

In place of electromagnetic motors, ceramic strips that can expand or contract when hit with an electric field are used, a technique known as piezoelectricity.

The problem of building these parts at a fly-sized scale was also an enormous obstacle. For example, the robot has no onboard power source – instead, it receives electricity via a thin wire connected to an external battery.

The solution to this is a groundbreaking technique that involves layering and folding sheets of carbon fiber, brass, ceramic and other materials, and then using extremely precise lasers to cut these sheets into structures and circuits. After that, the sheets can be assembled into extremely small but entirely functional devices in a single movement, just like a children’s pop-up book.